Tracing a Shortage: Stockings in the Second World War

The World War II Gallery at Anzac Square Memorial Galleries has recently seen additions to the Mementos screen’s content, from Lloyd Jones’s chess board to Sir Anthony Covacevich’s ashtray that was crafted from an aircraft engine piston. While interesting in isolation, these objects gain significance and intrigue when their history and context is considered, as well as the way they fit into their owner’s lives. The perfect example of this is the newly displayed package of liquid nylon powder which is, within itself, a rather ordinary looking envelope, yet it represents an ingenious war time invention. It also belonged to a young Brisbane woman, Cecily Lydia Fearnley (nee Sandercock) who led a very interesting life as an artist and author.

Cecily Lydia Fearnley was born in Brisbane in 1925 and was completing her schooling at Brisbane Girls’ Grammar when the war broke out. Moving to a technical art school at 17 years old, Cecily was unwittingly training for a future of important wartime work. Both her father and brother were already participating in the war effort: her father as a Divisional Engineer in the Telegraph's Postmaster-General’s Department, and her brother served with the RAAF from 1940-1945.

Remaining at home in Queensland, however, was not without its own worries, as fears of Japanese invasion escalated after the bombing of Darwin in 1942. Thus, Cecily was determined “to do something useful” for her country and found the answer working as a tracer at the US army headquarters in Brisbane. She drafted maps of site plans, camps and roads, and plotted where aircraft crashed so that bodies could be retrieved for burial. Due to her skill and dedication, she was promoted to the classified security section at just 19 years of age.

As the war came to an end Cecily moved on from map making, but could be content in knowing that she made an undeniably important and unique contribution to the war effort. Continuing to pursue her passion for art, Cecily commenced as an art assistant at the Queensland Museum in 1947 and was awarded the Queensland Naturalist Award in 2001. Only a few years after beginning at the museum, on 11 April 1953, Cecily married James Phillip Raymond Fearnley in Brisbane’s Albert Street Methodist Church.

On top of her achievements as an artist and naturalist, Cecily wrote a number of personal histories. This includes her own wartime experiences in Brisbane, her husband’s military experiences, and the war service of nurse and aunt-in-law Anne Phillips, all of which can be found in the John Oxley library collection here.

But how does Cecily’s story relate to the package of liquid nylon powder that she owned? Well, Cecily represents a cohort of young Australian women who were forced to grow up amongst wartime restrictions. Subsequently, they had to adapt their fashionable aspirations, or their simple desire to adhere to beauty expectations, to a limited array of items. Stockings were an expectation in a woman’s wardrobe, as they adhered to ideas of decorum and modesty, and added an air of glamour. While they had begun as a knee-high adornment, they gradually lengthened as hemlines shortened.

Although hosiery began as a clothing item for elite men in the Medieval period and were usually made of velvet, it was silk stockings for women that were highly sought after in the 20th century. Yet, it was only after the First World War that the delicate silk entered the price range of the middle class. But silk’s dominance was destined to be challenged, as in 1939 at the New York World Fair, DuPont made his revolutionary hosiery debut: the affordable, comfortable, and long-lasting nylon stocking. Within two years, 30% of the silk-stocking market was claimed by nylon. But women were not to have this new luxury for long, as all nylon was diverted to the war effort to make ropes, parachutes and tarps. Nylon even earned the title of the “fibre that won the war”. But women were now left with a dilemma. With nylon stockings off the market, and silk stockings rationed and expensive due to the loss of Japan’s silk trade, what were they to wear? The answer was an inventive liquid nylon (or, the stocking black market, of course).

Liquid nylon stockings acted as a makeup foundation for the legs that gave a sheer stocking appearance. This could be enhanced with a seam up the back of the leg, drawn with an eyebrow pencil. As the demand for liquid stockings rose, leg makeup bars began to appear in department stores to assist women with the choice of colour and application.

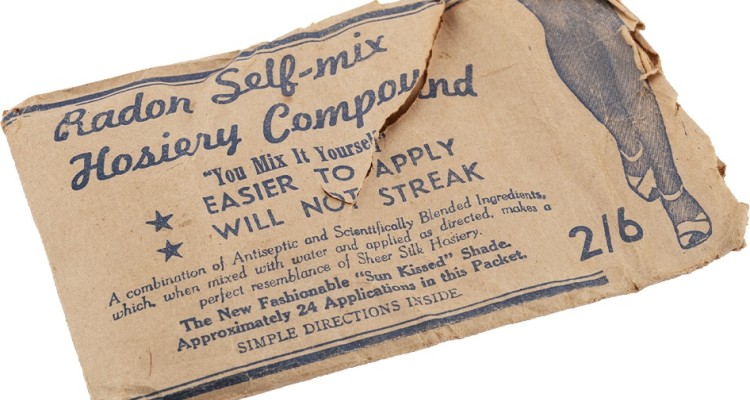

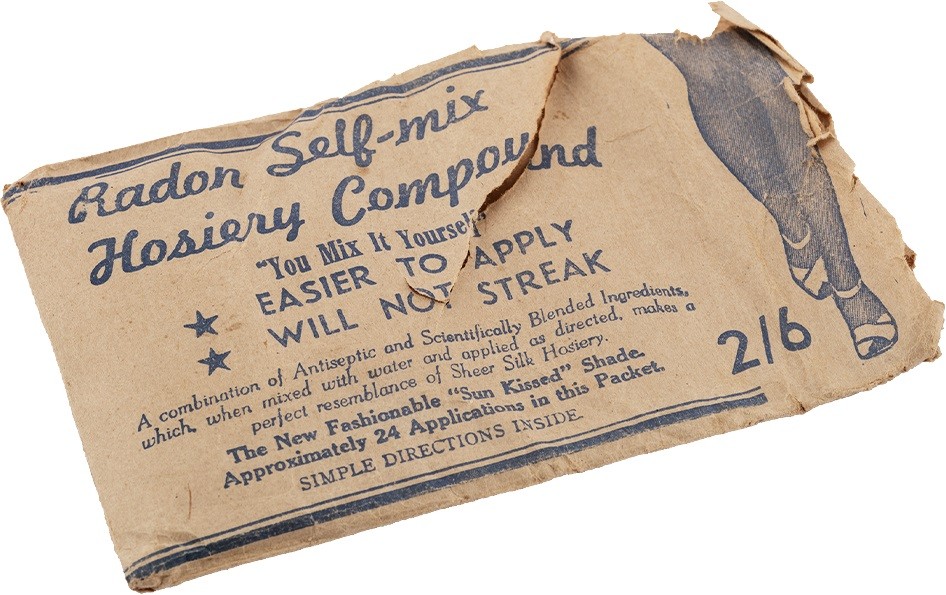

Although liquid bottles of the stockings were popular in America, such as the Leg Silque brand, it appears that the powdered form such as Cecily’s Radon package were used more commonly in Australia. Radon, the “honest Australian production”, instructs its users to simply pour the powder into a cup, fill it with water, and let it sit until the mixture becomes a creamy consistency. Then, while standing on newspaper, rapidly rub the liquid onto the legs and allow it to dry before brushing off the excess for the next use. In this way, the Radon package claims to have 24 applications for only 2 pounds and 6 shillings.

Although Radon claims it is made from a “combination of Antiseptic and Scientifically Blended Ingredients” that are “pure and hygienic” and actually contain “curative properties”, no specific ingredients are given on the package. However, there is evidence to suggest that some nylon powders were not as harmless as their companies claimed. For example, the Perth 1941 article in The Daily News suggests at least some women had trouble with liquid nylon products, as the article details a ‘specialist’s’ advice to those who claimed that the product had harmed their skin. The 1942 article in The Mercury also informed readers that liquid hosiery had been prohibited “because various essential chemicals were used in the manufacture of the stocking substitute.” On the other hand though, the Radon advertisement in The Farmer and Settler paper in 1942 suggests that Radon was different to the other array of “lotions, powders and creams” that were on the market, which had “dyes…that have been found to penetrate the skin and cause a rash.”

It is clear then, that this small package of Radon liquid nylon powder, now displayed in the Galleries, represents a much bigger story. Not only that of Cecily, a young Brisbane girl growing up during the Second World War and using her artistic talents to assist her country during wartime, but a much broader story of ingenuity during times of hardship and women’s resourcefulness in the face of limitations and under the pressure of social expectations. Each item displayed on the World War II Mementos Screen has its own interesting story. Come and discover them at Anzac Square.

References and Further Reading:

Edwards, D, (15 May 2019) ‘First Pair of Nylon Stockings Sold’, The Globe and Mail.

Fearnley, C.L, (2003) ‘War Time Experiences of Cecily Lydia Sandercock in Australia in 1939-45’, State Library of Queensland.

Fearnley, C.L, (2002) ‘Jim Fearnley’s Military Service’, State Library of Queensland.

Fearnley, C.L. (2002) ‘Anne Phillips’ War Service, 1939-45’, State Library of Queensland.

Patterson, T, (30 September 2015) ‘The Politics of Pantyhose’, The New York Times.

Spivack, E. (10 September 2012) ‘Paint-on Hosiery During the War Years’, Smithsonian Magazine.

The Daily News, (28 November 1941) ‘Specialist Reassures on Liquid Stockings’, The Daily News, Perth, WA.

The Farmer and Settler, (26 November 1942) ‘Around the Shops’, The Farmer and Settler, Sydney, NSW.

The Mercury, (17 September 1942) ‘No More Liquid Hosiery’, The Mercury, Hobert, Tas.

Touma, R. (26 November 2023) ‘“I wanted to do something useful”: the teenager who drew edible maps for Australia’s wartime pilots’, The Guardian.